The Coming Out Ring

Bill, a mutual friend Markie, and me in San Francisco (left to right).

Every year since my friend Bill committed suicide, his mother and I had exchanged Christmas cards. And I am one of those people who do holiday letters. As I have drifted apart from college friends, those annual missives are the only updates I get or give to them and some others in my life, including Bill’s mother. In the holiday letter of 1997, I had announced to the world that after years of hiding the truth even from myself, I had finally come to terms with being gay.

I had just moved to the Normal Heights section San Diego from where I had been living in northern San Diego County, in Carlsbad. The house that I was now renting was on the hill above the Qualcomm Stadium where the 1998 Super Bowl would be held, close enough to hear the blimp engines and we’d be able to walk out to my front porch to see the Blue Angels flyover and watch the fireworks show. I decided to throw a Super Bowl/house warming/coming out party.

When I packed for the move from Carlsbad to San Diego, I had vowed I would really weed things out. If I was never going to read that book or wear that shirt again, I’d donate it. Bags of clothes went to Goodwill and boxes of books went to the Carlsbad Library.

The Friday before Super Bowl Sunday I still had lots of unpacking to do to and I had promised myself that every single box would be emptied so I’d have Saturday free for party prep. I had about 15 boxes to go and was slicing into them, quickly dispatching whatever I found to the appropriate shelf, closet, or cabinet. Then it happened. I slit open a box that I moved to Carlsbad and from Carlsbad without having ever opened. It had stayed for years out of sight up above my car on the joists of the garage. I knew I was never going to wear the clothes that were in it or read the books or look at the photos hidden in it. In it were all of the things that reminded me of Bill. Photos of the trips we had taken together, music cassettes, books, clothes, and gifts he had given me over the years of our friendship. Shortly after Bill’s death, unable to deal with my guilt and sadness, I had sealed all remembrances of him away and I had no intention of opening that box either before or after the move.

Suicide is different. I have lost close friends to cancer and felt terrible, but I never felt guilty. I can’t cure cancer. I couldn’t have done anything to prevent the car accidents that claimed other friends’ lives. But suicide, rightly or wrongly, feels preventable. If I had listened better, if I had been a better friend, maybe it wouldn’t have happened. Bill’s suicide haunted me so badly that I couldn’t bear to think about him without it causing days of depression.

I opened that box and on top was a bicycling jersey Bill had given me. It made my heart sink. I hadn’t planned to deal with this box now or ever, but in my haste to finish unpacking, I had attacked the box without reading the magic marker warning on the top. Shit. I didn’t have time to deal with this. But the jersey wouldn’t release my stare. I had way too much to do and couldn’t spend time fixating on a stupid shirt. I should just re-seal the box and get back to work. Then I remembered my self-imposed dictum to get rid of anything I would never wear again. But I couldn’t throw it out. It was one of my last tangible reminders of Bill. A reminder I couldn’t bring myself to even look at, let alone wear, so I should just donate it to Goodwill. But I couldn’t give it away. I should just seal the box and deal with another time. But I had to deal with it sometime. I should just throw it out. And so it went, my wheels spinning in the same circle as I faced what I had avoided for years. I also thought of the absurdity of keeping a cycling jersey—my knees were too shot to ride more than a mile or two anyway. My days of riding centuries were over; that was something else Bill and I had in common, our knees had curtailed our serious cycling.

I got tired of standing over the box, but still couldn’t let go of the dilemma. I carried the shirt to the living room and held it as I sat and stared at it and replayed the options in my head. Donate it. I can’t. Wear it. I can’t. Only to dismiss them all and start over again. After at least an hour, maybe two, I grew tired of my stupid indecision. I needed to go pick up my mail from my P.O. box before they closed and I hadn’t put a shirt on yet that day, so I just decided, screw it. It’s just a shirt. Put it on and go get the mail.

Bill's ring

In that day’s mail was a package slip. I stood in line and gave it to the clerk who retrieved a padded envelope just slightly too large to fit in the box. On it was Bill’s mother’s return address. A month earlier, I had already received my once-a-year communication from her—a card with the usual short note, something to the effect of, “I hope you’re doing well” so I hadn’t expected anything.

With great curiosity, I opened the envelope. In it was a gold ring. I recognized it immediately as Bill’s. He treasured that ring and had worn it for years. It had been made for him by his great-uncle, a dentist in England who used scraps of dental gold in wax molds to make jewelry of his own designs. After Bill’s great-uncle’s death, the ring meant even more to him as a daily reminder of the man who had been his surrogate grandfather. Bill and I had that in common, also—we each had a special great-uncle who took the place of the grandfathers we both lacked.

After one trip to England to visit his mother’s family, Bill came back heartbroken. He said he had been helping his mother’s brother work in the garden and in the course of the digging and planting apparently the ring had slipped off his wet and slimy finger. He didn’t notice it was gone until they were done and he was washing his hands. They went back the garden and raked and dug and searched. They even borrowed a metal detector, but to no avail. Bill had lost the last piece of his great-uncle and there was no way to replace it.

In the package with Bill’s ring was a handwritten note from his mother. She said her brother had been working in his garden and found the ring. He thought she should have it. She received the ring the same day she got my coming out letter and she knew I had to have the ring. She said she was giving it to me by proxy for Bill and that she was happy that I had finally found the self-acceptance that Bill never had. Suddenly everything fell into place. The real reason Bill had killed himself.

I sat in the car and cried until I calmed down enough to drive home. It also seemed beyond coincidence that for the first time since Bill had died, I was wearing a shirt he had given me while I was holding his ring.

Bill’s death had always been a scab for me. Not an open wound, but a barely-healed scab over a wound I was afraid to go anywhere near for fear of causing damage too deep to handle. I had a hard time ever remembering the good times with Bill since the ending was so horrible and my guilt so overwhelming that I shut out thinking about him at all. With the ring, I felt like he had forgiven me (if there was ever anything to forgive) and I knew I could finally start to think of him without immediately going to the bad places.

When I got home, I called a friend of Bill’s in L.A. and asked how soon I could see him. Monday, the day after the Super Bowl, I drove to L.A. to have dinner with him. He and Bill had gone to high school together and lived together in Belgium for almost a year when they were trying to break into the ranks of professional track cyclists. I figured if anyone knew if Bill was secretly gay, he would. He said that even in high school, Bill’s friends had assured him that it was okay to come out. He’d still be their friend, and it would be okay. But Bill always vehemently denied being gay.

The memoir containing this and other stories

I asked why he thought Bill was gay and he ran through a list of stereotypical gay interests including liking Morrissey, Lucy, and Marilyn Monroe. The way he dressed and held his cigarette. I had noticed some of those things, but attributed the mannerism to being half English and spending so much time in Europe. (There is the old joke: Is he gay? No, just European.) The friend also said he wondered about my friendship with Bill and how quickly Bill and I became friends when we started working together and Bill at times saying things about me that crossed the line from friendship to crush.

The talk helped me understand so much. In my mind I replayed many of the moments I’d had with Bill and they made so much more sense now.

Once I sorted out the flood of emotions, I wrote to his mother and told her that far more than his ring, she given me back Bill. I know Bill is still with me. He is a part of me and I can enjoy the good memories without having to dwell on the bad. I cried for days when he died, but had been afraid to since; afraid to start again for fear I’d never stop. I finally let out what I had kept inside. It put one more piece of my old unhappy life behind me, to be even happier out of the closet.

I was able to unpack the rest of the box of Bill’s stuff. Wear those shirts again. Look at photos of him, have on display some of the other gifts he had given me.

I sent Bill’s mother her annual Christmas card about three years ago and a few days later got an email from a real estate agent in Pasadena. He said he was sorry to inform me that Bill’s mother had died. He said in addition to selling the house for the family in England, he had been asked to check mail and follow up on things that required it. His mother never got over the death of her only son so at least now she was at peace.

My eyes are moist and I am wearing his ring as I type this, and although still weirded out by the coincidence of the timing, but there has to be a message here: if I ever needed a final endorsement that I was doing the right thing by choosing to be happy for the first time in my life, Bill’s ring was certainly it.

I have had so many people ask about the ring over the years. Sometimes just holding out my credit card to pay in a store, the clerk has grabbed my hand and wanted to look at the ring. Some seemed to sense there is some magic to it and asked if it had a story. Once at a drug store, I started telling the story to the clerk and then I realized a line was forming at the register and I apologized and stepped aside and everyone in the line said, “No, this is good. Go on. Finish the story. Please continue.”

◇ ◇ ◇

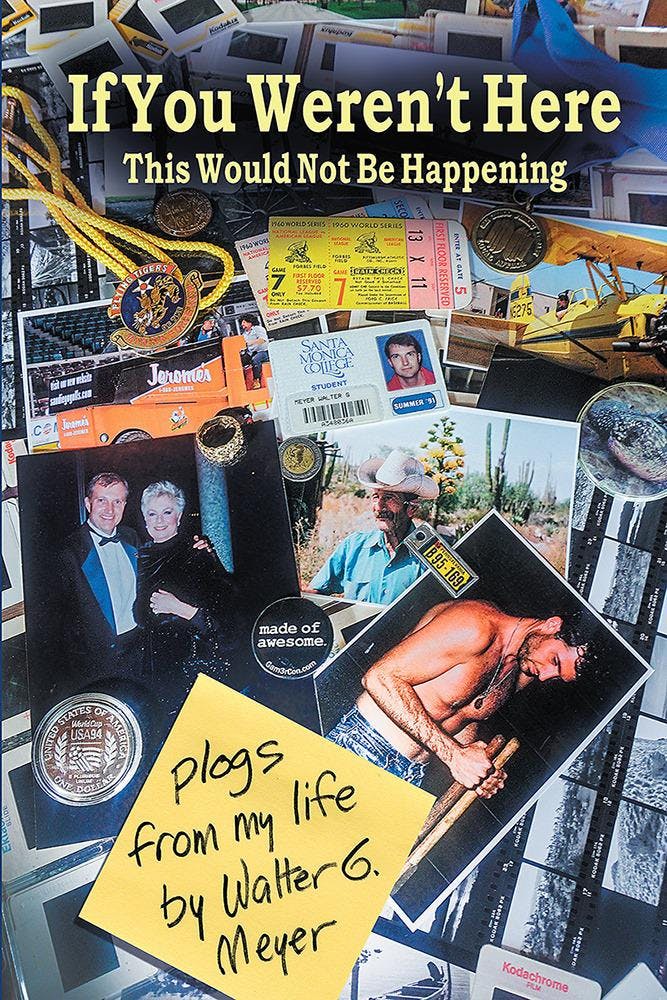

The story of The Coming Out Ring is abridged and adapted from If You Weren’t Here, This Would Not Be Happening: plogs from my life.

Walter G. Meyer is the co- or ghost-writer of six nonfiction books and his the author of critically-acclaimed, award-winning, and Amazon-bestselling gay-themed novel Rounding Third. He has been on radio and television programs including NPR and he has spoken at colleges, libraries and community centers across the country.

Mr. Meyer told his own coming out story in The Los Angeles Times, he has written for all of the major gay publications including Out and Advocate and he has written on LGBT topics for the mainstream press including The San Diego Union-Tribune and The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. His articles have appeared in Kiplinger’s Personal Finance, Orange County Register, Westways, Baja Explorer, and dozens of other magazines and newspapers. He is the co-author of a widely-produced stage play GAM3RS.

Originally from Pittsburgh, Mr. Meyer has a degree from the School of Communications at Penn State and currently resides in San Diego.

Post Info

Walter, this is so beautiful and moving. I resonate a lot with having jewelry that serves as a portal to another person's memories and life and stories.

@Shirley Man-Kin Leung Hi Shirley - Thanks for writing. As I wrote in the story, the ring does seem to have a magic power that draws people. They want to talk about it I get to talk about Bill. At times I find myself twisting the ring on my finger and memories come flooding back.